Yesterday and Today

By Tim Lambrinos

There are certain things that go better in life and continue to be undeniably recognizable by sound, taste or smell. And running ahead of the pack, there is one fashionable carbonated refreshment that continues to hold down the number one position worldwide. That is the classic taste of Coca-Cola that sits firm among soft drink consumers.

The beverage was developed in 1886 by pharmacist John Pemberton of Columbus, Georgia. It was first introduced with cocaine from coca leaves and caffeine from kola nuts.

Pemberton had been severely wounded by a sabre thrust to the chest while enlisted in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. His efforts to control his chronic pain led to morphine addiction. He developed the soft drink as a patent medicine in an effort to control his addiction.

In 1889, Pemberton’s formula and brand were sold for $2,300 (roughly $71,000 modern equivalent) to Asa Griggs Candler, who then incorporated the Coca-Cola Company in Atlanta, Georgia in 1892. The company continues to produce syrup concentrate, which is then sold to various bottlers throughout the world who hold exclusive territorial rights. One of the main manufacturing sites in Canada is located right here in Emery Village.

In 1961, a manufacturing plant opened on a new industrial road named Fenmar Drive over top of Joseph Crosson’s former farm. Surrounding the new factory, and abutting Signet Drive, there remained miles upon miles of farmland. The factory itself was situated on a 10-acre plot of land and had a floor space of 50,000 square feet. The additional land would accommodate space for future building expansion that was anticipated to occur down the road.

The manufacturing business was known as Beverage Canners Limited. The high-tech company would manufacture carbonated soft drinks and seal the refreshments into pop-up cans. The exterior of the plant was designed by Maurice Frisque of Finley W. McLachlan of Toronto. The administration offices are still magnificently visible on the second floor with a glassed-in gallery from which all canning and packaging processes are viewable. The factory initially opened with seven shipping and receiving doors for trucking service, plus four additional doors designated to accommodate railway shipping and receiving.

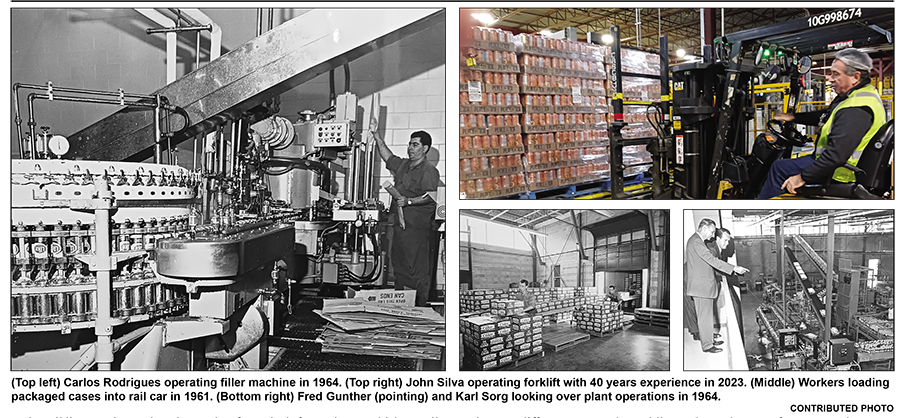

The rail line was located on the north side, or rear, of the factory. Rail cars were used to bring in massive quantities of sugar and syrup. The cars also served to send off finished products of cased cans. All these products were loaded by hand onto either trucks or rail cars.

The mainstay of the business was a 37,500 lb. capacity fibre-glass tank. It was made by Canbar Plastics of Waterloo, Ontario and installed to accommodate two grist loads of sugar. The sugar was pneumatically transferred from rail car to each designated tank by electronically controlled diverter valves, taking only 45 minutes.

A large machine called the Fluidizer Cyclo-Vac would draw the sugar from the tank to send it to the syrup mixers. Concentrates composed of various acids, colours, flavours and essential oils would have been first mixed in the customer’s own facility and brought to the plant. The product was pumped from the concentrate room to tanks in the Syrup Room, for blending. The formulation of the finished syrup would have been a jealously guarded secret. To avoid any breach of secrecy, the beverage companies provided their own lab technician to prepare their own particular formula.

There were two stainless steel mixing tanks equipped with electronic load cells in the legs. These cells provided the basic weight sensing system that made it possible to have a completely automated operation. The control system was arranged so formula information could be easily viewable on a control panel and recorded on a separate strip chart. Each cycle was completed automatically under push button control. The syrup was then transferred to one of the stainless steel holding tanks. All these operations are pretty much done the same way today as they were 60 years ago.

The first plant manager’s name was Karl Sorg. He had an operation manager named Dave Campbell and a technician named Fred Gunther who made up the company’s senior management team.

Around 1969, Coca-Cola Canada decided to stop being one of many customers of the canning factory. Other large soft drink clients included Canada Dry and 7 Up. Instead, officials at Coke decided to purchase the plant outright from Beverage Canners Limited. They quickly built a large addition to increase productivity for their own exclusive Coca-Cola canning operation.

Over the next two decades, Coca-Cola remained the number one brand worldwide until 1985 when they began to recognize that they had been losing significant market share to diet soft drinks and non-cola beverages for several years. Their own blind marketing tests suggested consumers preferred a sweeter taste, more like competing brands.

And so, the Coca-Cola recipe was reformulated. “New” Coke was introduced to the public that seemed to have a different taste. The public reacted extremely negatively to this rebranding experiment and as a result of enormous public backlash, “New” Coke was deemed to be a major flop.

Coca-Cola was reintroduced back to the public along with the original Coke formula within only three months, rebranding itself as “Coca-Cola Classic.” The results showed a significant return complimented by a substantial sales boost. This led to speculation that the New Coke formula scheme was nothing more than an advertising ploy to stimulate sales of the original Coca-Cola, which seems unlikely. The story of New Coke remains influential as a cautionary tale against trying to tamper with a highly established successful brand.

During the next few decades in Emery, the Fenmar Coca-Cola plant’s accountant was Derek Petit and the operation manager was Danny Crawford. These days, Coke Canada Bottling operates the Fenmar manufacturing site locally as an independently-run, family-owned business. A relatively new business, Coke Canada Bottling was formed only four years ago when new owners Larry Tanenbaum and Junior Bridgeman took over the reins as a Canadian-based joint venture. The company is a local bottler that makes, distributes, merchandises and sells Canada’s most-loved beverages. Coke Canada Bottling is in every province, with more than 50 sales and distribution centres and five manufacturing facilities. Over the past few years, the company has announced over $135 million in capital investments, including a $17 million investment into the Fenmar plant, for new equipment.

The Fenmar plant is proudly recognized as a Coke Canada Bottling facility that manufactures the most beverages in aluminum cans in Canada. The company’s other manufacturing facilities are located in Lower Mainland, B.C., Montreal, Calgary and Brampton. The local Fenmar plant produces and ships out about 50 million cases of cans per year, or the most in North America. Even with a greatly expanded facility than the original 1961 plant, the factory operates with 200 employees.

Today’s plant manager, Gareth O’Connell, along with production supervisor, Yeshwanth Balaji Babu, oversee operations with many more safety features than when the plant first opened up 60 years ago. Automation has also improved efficiency. Mandatory safety vests, eye and ear coverings and hardhats are a few of the measures now in place for all employees. And the shrink-wrapping machines and forklifts now replace a great deal of the labour that used to all be done by hand. But one thing still remains the same. That is the distinctive taste of Coca-Cola that probably never will be attempted to be rebranded again since there really is nothing better than a Coke.

So, have a Coke and a smile.