By Tim Lambrinos

Before the start of the 19th century, the natural environment around Daystrom Drive Public School was home to a large indigenous settlement. This local Indian village site was first documented and surveyed by United Empire Loyalist, Augustus Jones. In 1793, he accompanied Lieutenant Governor Lord John Graves Simcoe on horseback through this community in an effort to accurately map the Huron Indian pathway known as the Toronto Carrying Place. Simcoe was interested in mapping the roadway for potential military purposes. They were accompanied by a few natives, three army officers and 12 soldiers.

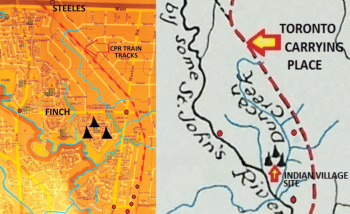

This 28 mile route they tracked travelled on the east side of the Humber River from Lake Ontario to the and marsh. The trail had previously been discovered by Etienne Brûlé in September of 1615. The winding sections of modern-day Weston Road, from Sheppard to Wilson, are part of the original trail.

However for topographical reasons at Weston and Sheppard, it was noted by Jones that the trail diverted slightly northeast. This was designed purposefully by the Huron makers to reach higher ground and cross smaller tributaries instead of the much deeper Emery Creek.

These tributaries currently run underground through large pipes that go below the CPR train tracks and Highway 400. Cross referencing Jones’ original chartings, it appears the Indian trail route runs through Emery Village on the land that would become the CPR train tracks in 1870. At Steeles Avenue, the trail appears to take another turn directly north to what is now known as Pine Valley Drive.

During Simcoe’s time, the core transportation waterway was known as St. John’s River and also as the Humber River. Historians recorded that Simcoe, Jones and co. paused during a day of surveying along the banks of Emery Creek in order to prepare a picnic with a “crayfish supper.” This historic location is more than likely near to what is now Finch and Weston Road. The creek was recorded in Jones’ survey as “Duncan Creek” in likely anticipation of Simcoe granting the heavily forested land to William Duncan III. William III later purchased large plots of land in Emery for each of his four brothers; James, George, Adam and John. The creek was later renamed Burns Creek prior to being known under the current name, the Emery Creek. Jones also recorded in his survey that an “Indian Village Site” was situated on the land now populated by Lanyard Road, Windhill Crescent, Lindylou Road and Legume Road.

Augustus Jones took up the practice of employing Mississauga natives during his surveying and expeditions. As a result, he became trusted by and learned the languages of both the Mohawk and the Mississauga Ojibwa nations. He served as a functioning bridge between Simcoe’s government and the indigenous nations.

Jones’ surveying and bargaining efforts for the government was indeed challenging and quite often dangerous. Most of the time Jones worked in the middle of winter when leaves from trees had disappeared and ground in the forest was intensely hard. He found it was easier to see through the dense forest in the wintertime with no leaves on the trees.

Although no physical description of Jones was ever documented, it is clear he was a vigorous man with an iron-clad constitution. He needed to be agile with a pack on his back, or carrying a birch bark canoe or thrashing through the deep snow with his snowshoes. In his early forties on April 27, 1798, he married 18-year-old Sarah Tekarihogen (Tekerehogen) – the daughter of Mohawk Chief Tekarihogen.

Uncovering and showcasing local indigenous history has been an initiative of the Emery Village BIA – now close to achieving a new indigenous park for the community. As a result of the new development at Finch and Weston Road, a location was selected on the east side of Weston Road in the hydro corridor. The park proposal is currently being reviewed by the City of Toronto.

The park will highlight the rich history of indigenous people from the early days of the community. The building of an indigenous park in Emery Village, complete with artistic and historic markers, is a venture that the BIA has taken on in hopes of creating a grand attraction.

As well, the BIA has made efforts to expand the concept of the project by urging the city to build pedestrian and cycling connections to link communities together and potentially hold outdoor recreational events. The park is expected to increase the profile of Emery Village and promote local business. As well, the park could enhance local pride by properly acknowledging the area’s native history. The Emery Village BIA is committed to forging ahead with plans for the park.

Residents Barry and Jenny Flude have lived on Windhill Crescent for 52 years and their entire family have always utilized the nearby ravine that could potentially lead to the park. The Fludes originally came from Belfast, Northern Ireland and their three children (Stephen, David and Karen) all grew up in the community and went to area schools. Barry and Jenny are also members of the congregation at St. Stephen’s Presbyterian Church at Weston Road and Verobeach Boulevard.

Their children, and now grandchildren, have regularly visited the local ravine for recreational gatherings in both the winter and summer. The Fludes recently took a hike down the ravine for a visual inspection of the completed storm water retention ponds with their daughter Karen and granddaughters Sydney and Hayley. The ponds now occupy a former flood plain behind Storer Drive and St. Lucie Drive.

The connecting cycling and walking trails have all been paved and the family were thrilled to see the completion of these pedestrian connections in the conservation land. Barry Flude still maintains reservations about the harmfulness of the pond water, the dimensions of the berms and their positioning.

The proposed indigenous park should connect these series of surfaced walking and cycling trails that would link the Humber River to Finch and Weston Road. The official opening of the paved trails and bridges is expected to occur in the Spring of 2019 and the Emery Village BIA will mark it with an opening ceremony.

But feel free to get outside to enjoy and explore the trails now. Perhaps even to distinguish the same seasonal environments, sights and sounds that our first nation inhabitants, Jones or even Simcoe first experienced when they initially arrived in the ravine hundreds of years ago. And be ready, perhaps, for exciting local enhancements arriving in our community.